Michael Heeney

By Joseph Bruchac

Stories remember when people forget. That is one of the many lessons that I’ve learned over more than 6 decades of listening to and then telling the stories that have linked our people to this place for thousands of years.

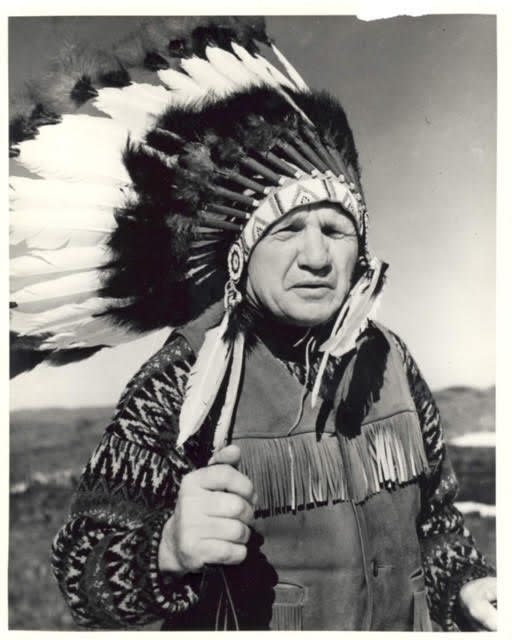

Maurice Dennis, whose Abenaki name was Mdawelasis (Little Loon). Eagle feather head dresses were not an old tradition in Abenaki communities. However, in the Northeast, throughout much of the late 19th and first three quarters of the 20th century most Native American tribal people wore plains style head dresses because of expectations from the general public.

Decades ago, one of my friends and teachers Maurice Dennis, whose Abenaki name was Mdawelasis (Little Loon) and was then living in Old Forge, New York, showed me the story held in the shell of every turtle. “See,” he said, “Count how many plates there on that turtle’s back. You’ll see there’s 13, always 13. That’s to remind us of two things. First of all, there used to be 13 Abenaki nations. Now there’s just one. And, second of all, there are 13 months in every year. Turtle remembers what we forget.”

Thinking of remembering, our stories are always told for at least two reasons. The first is to entertain. Although some stories were meant to be told all year round, a number are only told in the winter, when the days are short and the nights are long, when the wind is cold and the snow is deep. What better time to sit by a fire—not just back then in our bark lodge but today in our modern homes—and hear a story well told? I’ve often heard it said that good stories can help you through the hardest winter. The second reason to tell a story is to teach. A lesson conveyed through a well-told story is much more likely to be remembered. And even if the lesson is not immediately understood, that memorable story stays with you a long time and eventually may make its point. If children misbehaved, rather than punishing or scolding them, a lesson story might be told. When someone is harshly punished, they may only remember the pain of that punishment, not the purpose. But a story leads toward understanding.

Greg Danford

When Azeban, the Raccoon, the trickster character in many of our lesson stories gets himself into big trouble by being greedy or boastful or foolish in some other way—such as trying to shout louder than the sound of a waterfall and eventually getting too close to the edge and falling in—that story can teach a child making a similar mistake to not behave like the trickster. Don’t be like Azeban!

Our stories also point out truths about the natural world. More than two decades ago I did a storytelling program at the Lake Champlain Festival with John Lawyer, a Mississquoi Abenaki. I’ll never forget one brief story he told in which he pointed out that the eyes of the wolf, the bear, and the mountain lion are in the front of their heads. “That,” he said,” is because they are hunters, following a trail But the eyes of the deer and the rabbit are on the sides of their heads so they can see all around them because they are the ones who are hunted.” John paused then and looked at the audience. “We human beings have our eyes in the front, just like the wolf and the bear, and the mountain lion. We, too, were made by the Creator to follow a trail.”

Our Abenaki stories teach us not just about our lives and those of the many beings around us, the animal and plant people and we human brings, but also about the very shape of this land and its waters, this part of New England called Vermont, this place we know as Ndakinna—-Our Land.

Dave Gibson

Many of our stories are told throughout the wide region of the Wabanaki homelands. So it is that I’ve heard Abenaki stories from various native elders throughout New England, eastern Canada, and even northern New York state. Our people have always done a lot of traveling. Where Europeans tended to build a house and put down roots in only one place, it was the Abenaki tradition to travel seasonally and have more than one residence. Plus, the colonial wars between the French and English often displaced our people. Many ended up in Mission villages in northern Vermont and southern Canada—such as Mississquoi (Swanton) and Odanak (formerly St. Francis) in Quebec. What had been numerous tribal nations in present-day Vermont and New Hampshire ended up blended together as western Abenaki.

(Our people, the four currently state-recognized tribes of Vermont, have been called the Western Abenaki. We are very close cousins of the Penobscot people of Maine. Along with them, the Passamaquoddy, the Malecite, and the Mi’kmaq, our five nations are called the Wabanaki, the people of the Dawn. That name of Wabanaki, in itself, tells a story, reminding us of the promise of each new day and of our connection to light and life.)

Although many of our stories are told throughout New England, a number of them are located in or deeply connected to Vermont. Some are held in the names of places on maps of the state. Winooski is one. Winoos means onion and ki means place or land. It tells us that the Winooski area was a place where wild onions grew and could be gathered. The falls on the Winooski River is where, I was told, Azeban tried to outshout the water and was swept away.

The Connecticut River that flows between Vermont and New Hampshire carries another of our Abenaki place names. Kwani means “long.” Tewk is “river.”

One Abenaki story tells us how the Adirondacks got their name. As it was recorded (in Abenaki and English) in the 1932 volume Abenaki Indian Legends, Grammar and Place Names by Henry Lorne Masta, in 1790 a group of St. Francis Abenaki Indians from Swanton, Vermont were intercepted by a party of Iroquois near Saranac Lake. Rather than attacking each other, the two parties remained on guard.

Chadwick Estey

Finally the Abenakis, being very hungry, began, one at a time, to eat the pith of a pine tree after which they decided to fight and at once started on a wardance shouting and yelling. The Iroquois slyly withdrew and when the Abenakis perceived that their enemies were leaving they cried aloud “Magowak, Magowak” “Cowards, Cowards,” and that is the reason why the Iroquois are still called Maguak. In return they called the Abenakis “Adirondacks”—bark eaters.

(The word in that story used by the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois people of the Kanien’keha’ka nation was anentaks, their word for a porcupine, literally “the bark eater.” Anentaks became Adirondack. And it is also true that the name “Mohawk,” which does mean “coward,” is derived from the Abenaki language. One further linguistic note--the name Saranac comes from the Abenaki word for sumac.)

Back in the late 1980s, the Vermont Abenakis were attempting to regain traditional fishing rights as part of our struggle to obtain government recognition. At that time, the state of Vermont said that there were no real Native Americans in the entire state. In fact, despite our presence and oral traditions (and a wealth or archaeological evidence) Vermont said there never had been Indians in the state. Our people deliberately fished without licenses in order to be charged with breaking the law. We then took our case to court where we pleaded aboriginal rights to fish without a license.

I mention that case, because I was called in to testify as a storyteller. I told a number of the stories I have learned over the years, stories which spoke to our long tenure and relationship with this place now called Vermont. One story was the creation of Lake Champlain, one of our oldest stories and a tradition truly rooted in the land itself. The lawyer for the state of Vermont kept objecting. He kept tried to debunk my storytelling by saying “isn’t it like a game of telephone where every time something is whispered for one person to the next it changes?”

I replied that it certainly was not. None of our stories are whispered, but they are told out loud and heard not just by people who never heard that before but also by our elders who will correct us if we tell them wrong way. They were stories held by the people and, I said at the beginning, stories that knew more than any storyteller. Like the plates on Turtle’s back, they remember when human beings forget.

That case was won by the Abenaki nation. In August of 1989, Vermont District Judge Joseph Wolchik ruled that we had still retained our aboriginal rights to fish without a license, rights dating back 11,000 years. It was an important step towards our eventual recognition as authentic indigenous people. And while there was much more evidence of our legitimacy as the descendants of the aboriginal people of Ndakinna, I like to think that my stories—our stories—played a part.

Ktsi Nwaskw, the Great Mystery, put two ears in the head of Odzihozo, the first one in the shape of a human being. But Odzihozo was given only one mouth. It is a reminder that we must listen twice as much as we talk. And what we have listened to for more than 11,000 years are stories, stories that remind us where we live, who we are and how we should behave. Our Abenaki people know that is still true to this day. When we share our stories with each other--and with all Vermonters and any who visit our beautiful state-- that is one of the lessons we wish to teach.

Listen. And keep listening.