By Fred Wiseman

The Winooski River winding through the Intervale. Photo by Caleb Kenna

The Winooski river is one of the state’s most significant. Starting in the town of Cabot and winding 90 miles west to Lake Champlain, the river runs through the capitol in Montpelier, carves a swath through the Green Mountains wide enough for I89 to run through, and reaches the Lake at it’s mouth between Burlington and Colchester. The river is named for its stretch through what is now the city of Winooski, home to early Native American settlement(s) whose inhabitants found the falls, floodplains, and forests particularly hospitable. Vermont has lost most of its Abenaki place names over the last few centuries, but this is one of the few that remain. The word means, “Land of onions” or “Place of the wild onions”, an important spring and summer food of the local Indigenous community.

The lower Winooski Valley has been occupied since the late PaleoIndian Period, over 8,000 winters ago which we know due to the discovery of hunting tools that were used on large game animals. For Native peoples, the series of falls and cascades beginning at the Salmon Hole above the Burlington Intervale -- and stretching several miles upriver -- were the reason for settlement in the region.

Local settlements such as the Winooski Site could exploit the amazing ecological diversity in the area. Archaeological discoveries hint that transient individual families first camped in the area following the natural cycles of fish, game, and plant resources; but slowly became sedentary and formed larger, longer-lasting communities as they learned how to properly harvest, process, store and consume the natural bounty of the area.

The Intervale continues to be a fertile agricultural land to this day, with several farms operating within Burlington City limits. Photo by Bear Cieri.

Below the Falls was what we now call the Intervale, a wide, lush area of fertile floodplains suitable for corn, beans and squash agriculture. These plains were bordered by marshes and sloughs with abundant waterfowl, muskrat, beaver to hunt, wild rice grain to harvest and the starchy tubers of and tuckahoe (Peltrandra virginica) and arrowhead (Sagittaria spp.) to collect. The floodplain above the falls to the east stretched through the wide floodplain of the Richmond area, a gateway to the Green Mountains providing excellent hunting grounds.

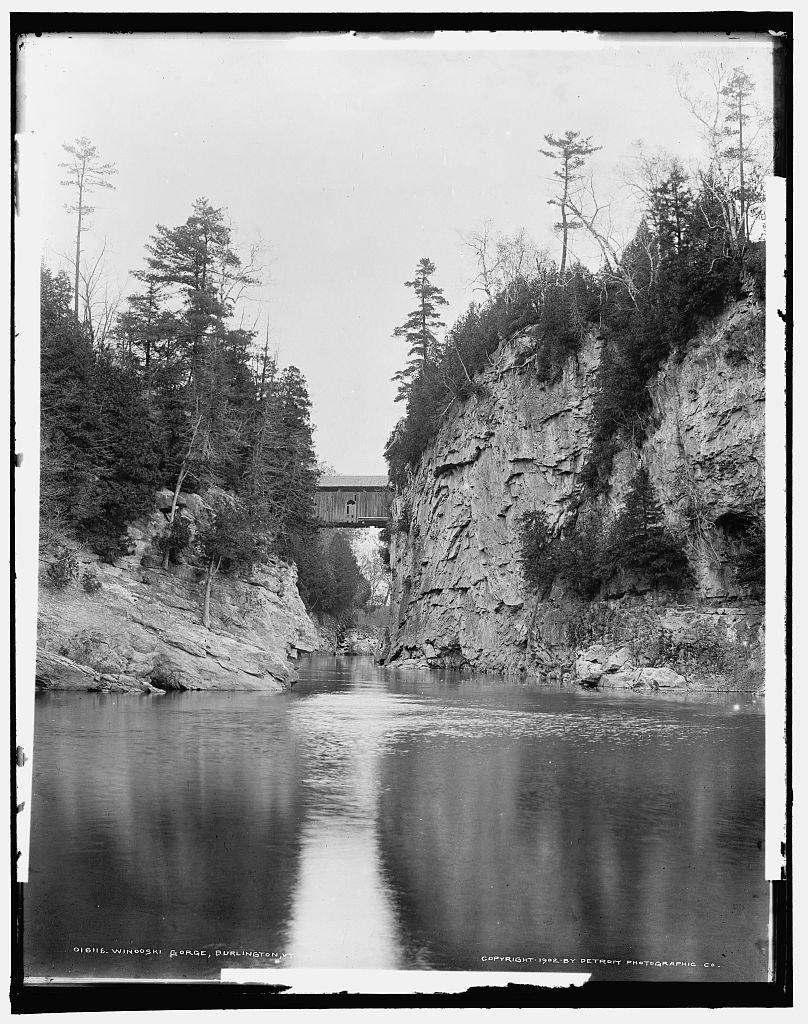

Winooski Gorge, 1902. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress and Detroit Publishing Co.

Fishing the Salmon Hole in 2020, Photo by Bear Cieri

Winooski falls, just west of the bridge to Burlington, formed a natural spawning area for many species of fish that swam up the river in the spring. The Salmon Hole is named for the salmon that congregated below the falls, but walleye, sturgeon and white suckers were also important. The suckers, known as the “garden fish,” were traditionally collected during their spring runs for fertilizing the floodplain fields.

Based on archaeological evidence found at the Winooski site, the ancestral Abenaki people collected large amounts of berries, fruits, nuts, and seeds form the nearby forest as well. They also practiced long distance trade; some stones for Winooski-area projectile points would have come from as far afield as New York, Pennsylvania, Quebec, and Maine.

The Winooski Falls had direct access to Lake Champlain, but was far enough upstream so that it was hidden from war parties that began infesting the region about 600 winters ago. From Lake Champlain, it was an easy canoe portage to the Hudson and St. Lawrence Rivers, and the Winooski trail went through the gap in the Green Mountains to the White and Connecticut Rivers and the East.

Unfortunately, the early European contact period was complex and disastrous for the Ancestral Abenakis of Winooski. First, European diseases swept down from the St. Lawrence Basin in the 1500’s decimating the population, then refugees fleeing genocide in New England flooded the region in an attempt to find safety -- just at the time that the political turmoil encouraged warfare with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) to the southwest. A rapid population decline followed, and by the 1800’s the remaining Abenaki people had to blend with the settler population or adopt new, non-Indian identities such as “Gypsies” or “River Rats.” There was a small 19th and early 20th century Winooski Valley community called Moccasin Village, that has been studied by Abenaki scholar Judy Dow. Today, there are several beautiful ash splint baskets, and other artifacts from Winooski area testifying to this continuing presence around the turn of the 20th century.

Winooski Falls in the early 1900s. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Interestingly, the 19th century mills at Winooski Falls attracted Abenakis (and Mohawks), as well as large numbers of Quebecois from Canada looking for well-paying jobs, thereby enriching the Indigenous diversity of the area. Today, the nearby Vermont Indigenous Heritage Center in the Intervale, a mile from Winooski as the Eagle flies, is a magnet for Native culture in the region, sponsoring classes, workshops, ceremonies and living history events. According to the 2010 Vermont Census there are about 30 people in Winooski who identify as Native American, and several are quite active in Abenaki cultural revival and politics. And so, Winooski has not only one of the few Vermont Abenaki place-names, but had and continues to have a deep and wide Native Legacy which needs to be acknowledged, and celebrated.